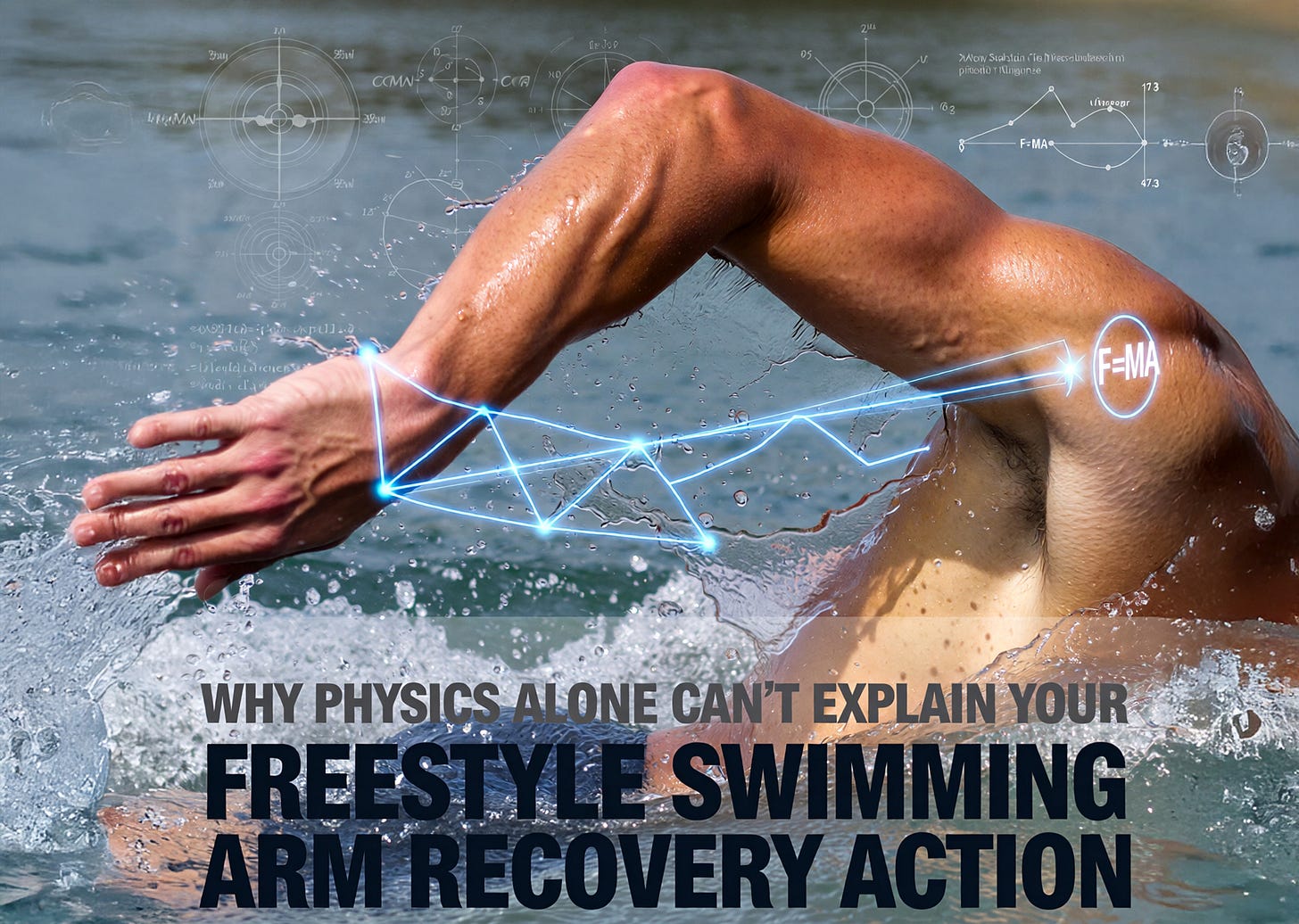

Why Physics Alone Can’t Explain Your Freestyle Recovery...

(A respectful reply to last week’s feedback)

Hey Swimmers,

Last week’s blog on arm recovery prompted some excellent discussion - including a detailed response grounded in physics and the principles of angular momentum.

It’s the kind of thoughtful engagement that makes writing these posts so rewarding.

Interestingly, this same line of thinking often appears in practical coaching settings too.